You’ve probably heard the term mindfulness bandied about, whether by yoga instructors or medical doctors, school teachers or businessmen – it’s an idea that seems to be sticking around. Depending on your knowledge and beliefs, you may be sceptical about the term, or maybe you’re just curious what all the fuss is about?

What is mindfulness?

There are various definitions of mindfulness, because it’s a notoriously slippery and ephemeral concept. According to US-based science publication Greater Good, mindfulness means, “maintaining a moment-by-moment awareness of our thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations and surrounding environment, through a gentle, nurturing lens.”

Meanwhile the Australian Government’s Health Direct tells us that mindfulness means, “paying full attention to what is going on in you and outside you, moment by moment, without judgement.”

Mindfulness app Headspace, which has listenable guided sessions, defines it as, “the idea of learning how to be fully present and engaged in the moment, aware of your thoughts and feelings without distraction of judgement.”

In academic psychology, legions of papers continue to be written attempting to define the concept – so if you’re not fully across it, you’re not alone.

What most definitions of mindfulness have in common are:

- Presence – a sense of being aware of the present moment, and the sensations and thoughts in your mind, body and surroundings

- Attention – attempting to focus attention on the here and now, rather than allowing thoughts to drift away

- Judgement-free – the idea that you observe and experience your internal and external environment without making a judgement about what is going on.

Mindfulness has links to Buddhism, and to the idea of meditation, but unlike many forms of meditation, mindfulness in modern Western psychology is not considered a spiritual practice but a secular one – a psychological exercise, in a sense.

There are all sorts of ways to practice mindfulness, but commonly you might sit, cross-legged or on a chair in a quiet space, close your eyes and practice breathing deeply for a set number of counts, focusing on your breath and allowing your mind to quieten.

The science behind mindfulness

Because mindfulness is quite hard to define, and probably something you experience rather than explain, it can seem a little wishy-washy to people unfamiliar with it. However, there is a scientific support base for claims that mindfulness benefits mental and physical health.

For example, it’s known that mindfulness – especially practiced over the long-term – can dampen activity in the default mode network, the brain region most commonly involved in self-obsessive or anxious ruminations. Dampening activity in this network can induce a calmer state, fewer racing thoughts and a greater sense of presence in daily life.

Mindfulness over the long-term is also shown to reduce activity in the amygdala and increase the connectivity between the amygdala and prefrontal cortex, alleviating the symptoms of stress.

There is also some evidence that consistent mindfulness can potentially boost your working memory, a brain function that can often be impaired by repeated stress.

It’s important to note here that mindfulness isn’t some magical pill you can take that will banish your stress and anxiety and cure your depression.

Current analysis suggests that mindfulness is not any more effective than other lifestyle activities – like exercise, therapy and drugs – in treating mental health problems. That is to say, mindfulness can be good for you, and is a great practice to incorporate into a broader pattern of self-care, but the evidence so far doesn’t prove it a ‘quick-fix’ all on its own.

What does mindfulness help with?

Mindfulness can be helpful in alleviating common symptoms of mental health issues, or in promoting self-awareness and calm.

Common benefits of mindfulness include:

- Wellbeing and stress relief – the neuroscience of mindfulness shows that it can reduce the symptoms of stress or anxiety when practiced over the long term, at the level of brain plasticity. It can also reduce stress simply by allowing you to become more aware of thoughts and feelings, less attached to them, and more in control.

- Reduction of rumination – mindfulness can reduce the prevalence of pervasive or racing thoughts, meaning it may help you to stop obsessing over a thought or a worry.

- Gratitude and appreciation – the benefits of mindfulness may also open the door to allow a greater appreciation for daily life. If you spend less time worrying and ruminating over issues, it can be easier to cultivate daily contentment, improving overall wellbeing.

- Emotional regulation – there is evidence that mindfulness can assist in the management of powerful or complicated emotions, preventing outbursts or unmanageable emotional responses.

- Relationships – mindfulness has been shown to correlate with relationship satisfaction in some cases, and to bolster the ability to communicate and engage with other people respectfully and empathetically.

- Self-awareness – there is some evidence that mindfulness can bolster the brain region associated with self-insight, meaning practiced in the long term it could help you to build a sense of self-awareness, and perhaps even self-love.

How to practice mindfulness

There are all sorts of ways to practice mindfulness. You can practice mindfulness by sitting down and actively engaging in a mindfulness activity, but you can also practice mindfulness in everyday life as you go about other tasks. Most important is simply cultivating that calm, non-judgemental awareness.

If you need a little guidance, there are all sorts of practices – spiritual and secular – that can help you.

1. Traditional practices of mindfulness

Traditional practices like yoga and tai-chi cultivate mindful awareness through movement, incorporating spiritual beliefs. While it’s certainly possible to practice yoga and even tai-chi as primarily physical activities, it’s important to know and be respectful of the roots of these practices, which lie in the ancient belief systems and cultures of Nepal, India, China and other parts of Asia.

2. Mindfulness apps

There are mindfulness apps that offer guided meditations. These can be long or short, geared towards addressing specific concerns or issues, or simply one-size-fits-all. They can include music and sound, or simply a soothing voice. Commonly used apps include:

- Headspace offers guided meditations as well as physical exercises and even sleep stories, all designed to improve mental health and wellbeing. It has a basic free version, or a fuller version with more offerings for between $7.67-$19.99/month depending whether you choose an annual or monthly subscription.

- Calm has a similar offering of guided meditations, many of which focus on improving the quality of sleep. Expect soothing sounds like raindrops on leaves or waves washing the shore, alongside guided meditations and stories. It costs $79.99 annually.

- iBreathe guides you through meditation by focusing on breathing. Breathing is often seen as an anchor for mindfulness, and can help you focus and cultivate awareness. The basic app is free.

- Oak is a free app that also offers meditation and breathing exercises.

3. Mindfulness classes

There are many organisations that offer classes in mindfulness, especially local meditation centres. Search for a suitable one near you, and give it a try.

4. Mindfulness in therapy

Many Life Supports therapists are trained in teaching and instructing mindfulness, as part of the tools taught to regulate your emotions and thoughts.

Some people prefer to have a professional walk them through the practice, so that they feel more confident in practicing it themselves on their daily lives. It’s a habit of thinking that needs to be trained, so it makes sense that some people want help applying it to specific stressful situations that they bring up in the therapy room.

5. Some simple mindfulness exercises

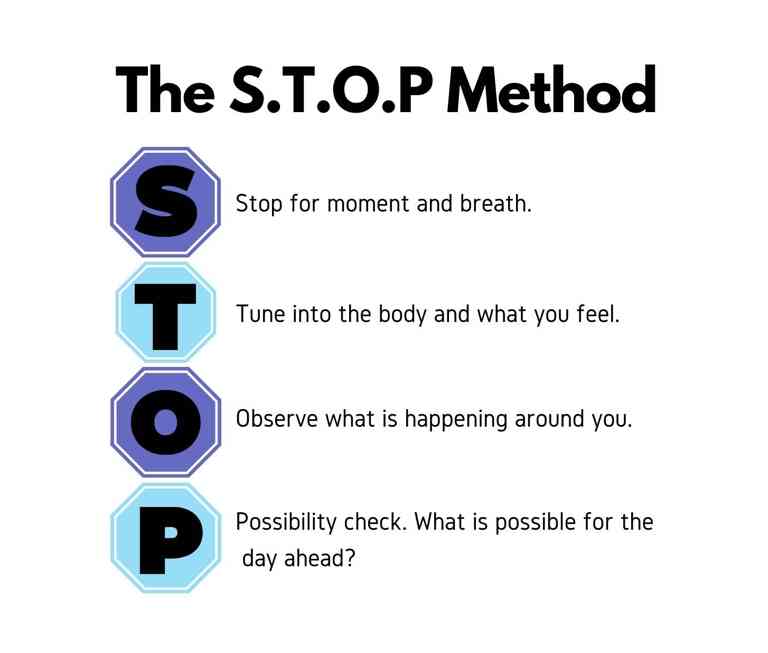

The STOP. method:

Mindful breathing:

- Sit somewhere comfortable, with hands on your lap

- Take in a deep breath, and exhale fully

- Begin counting your breathing, inhaling for 5 counts, exhaling for 7

- If it works for you, you can hold your breath at the top of the inhale or at the bottom of the exhale, noting that you don’t need to do anything too hard or strenuous

- Breathe like that for five counts, focusing on your breathing and allowing any thoughts or sensations to drift past, rather than take up space in your mind.

Body scan meditation:

- Lie on your back with your legs long and arms at your side, with your eyes closed

- Focus your attention on the lowest point of your body – your toes – and slowly, deliberately scan upwards through the legs, the torso, down the arms into the fingers, up the shoulder and neck and eventually to the top of the head

- Notice at each point how it feels

- Once you’ve reached the crown of your head, let your attention go and relax.

Amalyah Hart

Amalyah Hart is a freelance journalist and content writer, specialising in science communication. She has a degree in Archaeology and Anthropology from the University of Oxford and has completed a Master of Journalism at the University of Melbourne. She writes on psychology, health and health policy, and the environment. She also works in public policy consulting, specialising in the healthcare sector.

Recommended Reading

Get help now

Appointments currently available

Open 8am to 8pm weekdays and 9am to 5:30pm weekends